While some managers may beat their benchmarks, occasionally with stellar returns, there is no guarantee they improve your wealth. Active managers are expensive, generate significant taxes, and will eventually under-perform their benchmarks. They concentrate investments in less than fully diversified positions in order to better their benchmark, thereby exposing your wealth to greater risk than you may know about or need. The concentrated positions can make your investments considerably more volatile than the indexes against which they are measured, encouraging irrational decisions driven by fear or greed.

As a rule, actively managed portfolios are significantly more expensive than passive funds (those that match an index). Large salaries and bonuses are required for the smart people who direct the management investment decisions. Lots of transactions are required to position the portfolio among companies, industries, and sectors as directed by their managers. These transactions incur commission charges from the brokers executing the trades and they suffer another meaningful but rarely mentioned expense known as the spread (the difference between what is paid for a stock and what it is sold for). The spread, which ranges from a few pennies to a half percent or more, goes to the market maker of a stock, and it dissapears from your wealth every time a stock is bought or sold. A study done by the Wharton School of Business in 1999 found that mutual fund trading costs, which are not reported in prospectuses, averaged .78%. That’s more than three quarters of a percent the managers have to clear just to beat their benchmark.

Typically, when you buy a mutual fund you pay a sales charge of as much as 5.75%. Add that to the internal expenses of the fund which can range between .25% and 2% and you begin to see the challenge of simply catching up to where you could start with an index fund. If you bought a typical growth fund and paid the 5.75% up front commission, and incurred an ongoing .7% internal fund expense ratio, your fund would have to clear 1.83% a year for five years, just to break even with the benchmark index. But wait, there’s more . . . don’t forget the .78% that Wharton says is hidden among mutual funds’ expenses. Are you beginning to sense the magnitude of the challenge? If a mutual fund is going to offer any value at all to you in improving your wealth, the manager must scale a hurdle of more than 2.6% annually just to match the return you can get by duplicating his benchmark with index funds.

What we’ve been talking about so far concerns the margin or amount funds' returns exceed or fall short of their benchmarks. Fund managers can employ all kinds of shenanigans between quarterly reports to improve their returns, and these actions usually subject the fund, and your wealth to more risk than is inherent in the performance benchmarks. One way to check is to compare the fund’s beta to that of its benchmark index. Beta provides a measure of the volatility of a security or a portfolio relative to a benchmark. If, for example, the manager of a domestic growth fund allocates say 15% of his holdings to international stocks, he has added greater risk in the form of volatility to his portfolio than is contained in the benchmark (i.e. currency, credit, and small cap volatility to name a few). His fund will likely carry a beta over 1.

Alpha on the other hand measures the fund’s ability to produce returns beyond those that can be captured through a combination of low-cost index funds matching the makeup of the fund. This measure provides a better gauge of whether the manager provides value beyond simply owning the indexes.

Vanguard, a champion of low cost index funds, recently did a study to determine the probability of selecting funds that offer superior alpha. In their introduction they note that “talented managers can deliver better than-benchmark returns, and it’s easy enough to identify managers who have produced alpha in the past. Unfortunately, these historical feats shed little light on a fund’s future."

The study used the Morningstar database of the returns of actively managed mutual funds from 1990 through 2010. They calculated alphas relative to the stock market’s four common risk factors, as outlined by Fama and French (1993) and Carhart (1997):

- Market risk factor (the difference between the returns of the broad stock market and risk-free U.S. Treasury bills);

- SMB risk factor (a measure of the historical difference between the returns of small- and large-cap stocks; SMB refers to “small [market cap] minus big”);

- HML risk factor (a measure of the historical difference between the returns of stocks with high book-to-market and low book-to-market values; HML refers to “high [book-to-market ratio] minus low”); and

- Momentum risk factor (the historical difference between the returns of stocks with the highest returns over the past 3 to 12 months and those with the lowest).

“The figure presents two sets of probabilities, one calculated from a database free of survivorship bias (which includes records both of existing funds and those no longer in existence) and a database that is survivor-biased (eliminates the funds which have ceased to exist). The results based on the two datasets were different, but both led to the same conclusion: The probability that the highest-alpha funds will remain the highest-alpha funds in subsequent periods was no better—and was sometimes worse—than chance. (In a random distribution, we would expect to see 25% of the top-quartile performers in that same quartile in future periods.)”

The study's authors noted “the survivor-bias-free dataset is more reflective of an investor’s real-world experience. An investor’s long-term challenge is to identify a fund that can both outperform and stay in business long enough to deliver that outperformance to shareholders.

If you are curious about why the beige bias-free probabilities are lower, the reason is simple math, notes the authors. While the numerators (top number) were similar in both datasets, the denominators differed. The denominator of the beige bias-free dataset included both surviving and non-surviving funds and was hence larger than the denominator of the blue survivor-biased funds.

The study concluded by saying “unfortunately, the quantitative evidence of this skill—alpha and other measures of historical performance—is of little help in identifying tomorrow’s superior performers. The elements that distinguish talented investment managers are difficult, if not impossible, to quantify in a simple metric. Active management is both art and science. Talent exists, it produces alpha, but its basis can’t be captured in a mechanical formula.

If your objective is to improve wealth, then it is fair to say that the odds are stacked pretty highly against you if you choose to go the way of actively managed mutual funds. They are expensive and are apt to underperform. But there’s another problem. The trading that goes on in their daily management and to accommodate buyers and sellers of the fund both generate significant taxable income. If you own mutual funds in taxable accounts, you will mostly likely be hit with short and long-term capital gains at year’s end even if you didn’t sell a share. That’s because mutual funds are required to pass their capital gains and losses to shareholders each year. These taxable gains can be material. Returns on average can be reduced by 2% or more. Taxes of this kind are a steady and unnecessary leak of your wealth.

A study by Blackrock reveals just how extensive the damage to your wealth the tax costs of active management can be. The table below represents the impact of various tax cost assumptions on a portfolio of $1 million growing at 8% for 10 years. You should not be surprised to find that the tax cost of some of the most popular mutual funds easily clears 2%. In the figure below note that the impact of a 2% tax cost annually can reduce your wealth by as much as $400,000 over a ten year period. These are losses or leaks that CAN BE REDUCED, AND POSSIBLY ELIMINATED.

In my 30 years advising clients, I have found that the most persistent wealth destroyer is emotions. Investors who make decisions based on fear or greed are highly apt to sacrifice big chunks of their wealth needlessly. Active management plays a significant role in contributing to these behavioral mistakes. As a performance manager for 25 of my 30 years I am all too familiar with the warning signs. “What do you think about the market ahead? “What do you think about gold?” “Should we buy some Apple shares – they’ve doubled in the last three years?” “My barber says he’s got a year’s worth of canned goods in his basement.” “Should we park some money on the sidelines until things settle down a little?”

The actively managed marketplace known as the financial services industry provides a cornucopia of choices from 'zero' risk to Katie-bar-the-door. They are sold by appealing primarily to clients' natural fear or greed, and all too rarely what is best for their unique wealth needs. And when investors make decisions on emotion they are apt to seriously impact their wealth.

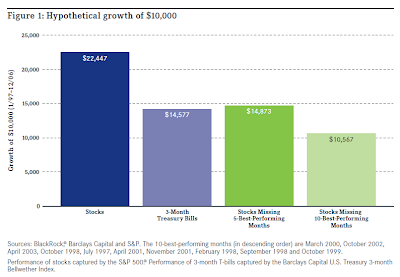

The figure below represents another study done by Blackrock. It represents the lost opportunity of sitting on the sidelines while the stock market (S&P 500) delivers its best months of performance. If I had a dollar for every time I heard “I wish I had gotten back into the market last. . . .”

The S&P 500 appreciated 124% from the period 1/97 to 12/06, yet those who missed the best 10 months of that 10-year period did not even beat the returns of 3-month T-Bills - a huge sacrifice of wealth lost while they hunkered down.

The S&P 500 appreciated 124% from the period 1/97 to 12/06, yet those who missed the best 10 months of that 10-year period did not even beat the returns of 3-month T-Bills - a huge sacrifice of wealth lost while they hunkered down.

When a managed portfolio experiences volatility beyond that of a widely reported benchmark, like say the S&P 500, then shareholders tend to panic and get out more often. Conversely, if a portfolio is constructed with market-efficient fixed and equity index funds or ETFs that provides more consistent returns, with lower volatility than say the S&P 500, then investors might be expected to stay invested, accumulating wealth for future needs – true?

The objective in building a market-efficient portfolio is to maximize the portfolio’s expected return for a given amount of portfolio risk, or alternatively to minimize risk for a given level of expected return, by carefully choosing the proportions of various assets, essentially fixed (bonds) and equities (stocks).

We use six standard model portfolios that are efficient relative to the capital market assumptions developed by Wealthcare Capital Management. People often ask how we did during the Great Recession, particularly over the 2008 market period. Because we are wealth managers and not performance managers my answers generally focus on the experiences of our clients. The short answer is that our clients were relatively content by comparison to other investors riding out the storm. Our phones did not ring any more than usual and we did not have to talk a single client out of bailing.

The graph below provides a visual explanation of why our more risk-sensitive clients remained confident. The blue line represents our most conservative portfolio (Risk Averse). The red line is the S&P 500 and the green line represents the 7-10 year US Treasury index.

Wealthcare’s studies have found that 7-10 year Treasuries provide the best offset to equity risk. When stocks are declining, Treasuries, historically rise in value, offsetting the potential wealth-erosion in their absence. As you can see below, the Treasuries (which represent 60% of the Risk Averse Portfolio) did exactly what they were supposed to do. They pulled the blue line - our client's wealth - up as the red line was pulling it in the opposit direction.

Wealthcare’s studies have found that 7-10 year Treasuries provide the best offset to equity risk. When stocks are declining, Treasuries, historically rise in value, offsetting the potential wealth-erosion in their absence. As you can see below, the Treasuries (which represent 60% of the Risk Averse Portfolio) did exactly what they were supposed to do. They pulled the blue line - our client's wealth - up as the red line was pulling it in the opposit direction.

When using the capital markets to accumulate and grow wealth, active management has numerous pitfalls. As wealth advisors we believe that by using market-efficient portfolios to control what is controllable; costs, taxes, and under-market performance, and by continually measuring uncertainty, we can confidently help our clients exceed their important goals and aspirations.

Have a great weekend.

No comments:

Post a Comment